By Josephine Hellberg MRSB, DPhil Physiology, Anatomy and Genetics student at the University of Oxford and science policy intern at the Royal Society of Biology.

Take part in a tweetchat on AMR from 15:00 – 16:00 GMT on Friday 18th November by following and tweeting with #AntibioticFuture

This week is World Antibiotic Awareness Week 2016; which has been highlighted with the intention of increasing global awareness of the threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and the importance of interventions to reduce antimicrobial use.

This week is World Antibiotic Awareness Week 2016; which has been highlighted with the intention of increasing global awareness of the threat of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and the importance of interventions to reduce antimicrobial use.

Antimicrobials are drugs that target infectious micro-organisms (microbes), such as bacteria and fungi, but also organisms such as the malaria parasite. The discovery of antimicrobials was one of the most important medical breakthroughs of the 20th century: reducing the incidence of infectious disease and revolutionising medical science; allowing procedures such as invasive surgery and cancer therapy to become commonplace.

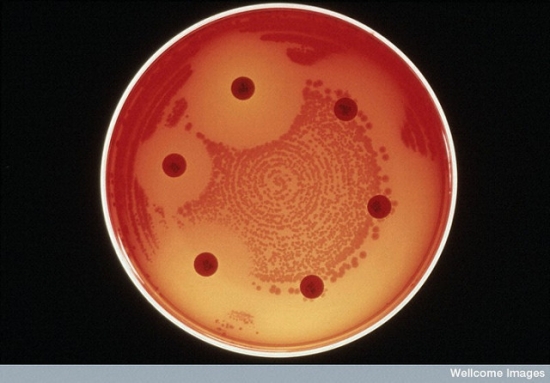

Antimicrobials can be natural or synthetic. They are called ‘antibiotics’ when they are produced by other micro-organisms, making antibiotics a natural part of ecosystem microbe-microbe interactions. However, this also means that AMR is a natural, biological phenomenon that is hard to avoid. As a result, increased antimicrobial use goes hand in hand with increased AMR. Indeed, AMR is now so common that doctors, scientists and governments warn that it represents one of the biggest challenges of the 21st century.

In September, the UN held a high-level meeting on AMR and produced a draft political declaration where they commit to develop ‘national action plans, programmes and policy initiatives’ to target the problem. Similarly, the UK Government has plans in place to tackle AMR. Their commissioned report (chaired by Lord Jim O’Neill): Tackling drug-resistant infections globally, was recently published. Together, the O’Neill report and the UN declaration both highlight that AMR is a worldwide problem that requires global recognition and action. Both also make recommendations to strengthen regulation and to promote innovation.

Improving regulation is important, because inappropriate antimicrobial use has contributed to the problem. For example, intensive farming practices can utilise large volumes of antibiotics to promote growth in animals produced for meat. However, some European Union countries have banned excessive use of antimicrobials in agriculture whilst retaining productivity – showing that such large scale antimicrobial use may not always be imperative for the production of commercially competitive meat.

Improving regulation is important, because inappropriate antimicrobial use has contributed to the problem. For example, intensive farming practices can utilise large volumes of antibiotics to promote growth in animals produced for meat. However, some European Union countries have banned excessive use of antimicrobials in agriculture whilst retaining productivity – showing that such large scale antimicrobial use may not always be imperative for the production of commercially competitive meat.

In addition to improved regulation, there is a need for increased global public awareness and education. A recent report published in the International Journal of Infectious Diseases describes a strong relationship between the poverty level of a country and its levels of AMR and says there is an ‘urgent need for the implementation of policies to […] curb inappropriate antibiotic use’.

Conversely, many related discussions focus on the exciting prospect of targeting antimicrobial resistance by increasing and incentivising innovation. Globally, there is a newly-formed partnership on antibiotic research and development that aims to develop new treatments and to promote their responsible use. The UK and Chinese governments have also started a global fund to tackle AMR, hoping to attract in excess of £1 billion to invest in research. Within the EU, the Innovative Medicines Initiative is funding several projects focusing on AMR.

The UK hosts a number of other initiatives focusing on AMR, such as the Nesta Longitude Prize challenge, which is crowdsourcing innovative diagnostics to combat infectious disease – as a method to reduce inappropriate antimicrobial use. Additionally, Antibiotic Research UK is a charity that tries to re-purpose certain antimicrobials, by identifying ‘antibiotic resistance breaker’ (ARB) compounds. These compounds act in partnership with the antimicrobials, improving their effectiveness.

To conclude, there is no shortage of ideas on how to solve the problem of AMR. A combination of innovation, regulation, and education may provide a realistic solution. There is also increased international recognition of the problem, but further collaboration is needed to make a global, lasting impact.

Find out more about AMR and the RSBs work with the Learned Society Partnership on Antimicrobial Resistance (LeSPAR).

Read our other blogs about antibiotics and AMR.