By Ian Selmes RSci MRSB

I have been a technician for 44 years. Thirty seven of these have been spent working in microbiology laboratories in four departments in three universities: London, Oxford, and now Newcastle.

Science is a dynamic process. Technicians need to update their skills if they are not to erode and eventually become redundant over time. An example of this is the evolution of DNA sequencing over the last 25 years.

Science is a dynamic process. Technicians need to update their skills if they are not to erode and eventually become redundant over time. An example of this is the evolution of DNA sequencing over the last 25 years.

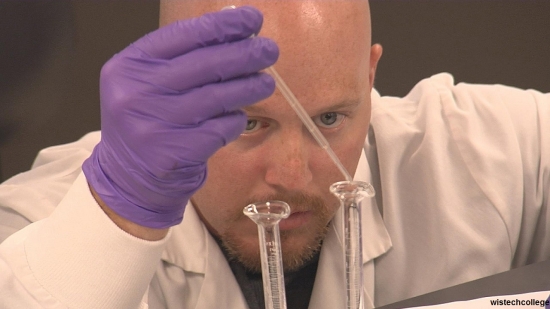

I first started sequencing DNA in 1990 using the existing Sanger method. Every aspect of this method was labour intensive from preparing the shotgun DNA libraries, running, fixing, and developing the gels, then digitising the data into the computer and using the first generation Staden computer programs to put the contiguous sequence together. It took two of us nine months to sequence 21.8kb of the major strain of Variola virus (smallpox).

In the mid-1990s ABI DNA sequencing technology superseded the Sanger method along with robots for preparing the DNA from shotgun libraries and improved computer programs to construct the contiguous DNA sequence and its subsequent analysis. This new technology allowed research laboratories working on the same microorganism to form a consortium to sequence whole genomes.

Last week I utilised the New Generation Sequencing (NGS) developed by the company Illumina to sequence 15 bacterial genomes. I took a few days to prepare the DNA samples and the MySeq Illumina sequencing machine took 65 hours to sequence the genomes! I already know that there is a robot available to prepare the DNA samples for sequencing!

The advancement of DNA sequencing technology is just one example of how science and technology has developed and changed during my technical career.

To enable the technical workforce in STEM subjects to maintain, develop and update their skill sets the Science Council and 10 of its professional member organisations, including the Royal Society of Biology, have now created a national framework of professional benchmarks to reflect the professionalism and skills of the technical workforce.

The benchmarks are: Registered Science Technician (RSciTech); Registered Scientist (RSci); and Chartered Scientist (CSci). Registration with the appropriate professional body at one of these benchmark levels will give you professional recognition and status. To maintain your status you will be required to provide evidence of ‘continuous professional development’, (CPD) each year. You will also be able to use CPD to develop your skill set to the next level of registration as your experience and updated education evolves, perhaps by utilising courses provided by HEaTED.

Employers are starting to utilise and quote these professional benchmarks in job advertisements. If you can prove you are professionally registered and can demonstrate that you have been doing CPD this w ill give you a selective advantage.

ill give you a selective advantage.

Many technical posts in universities are supported by soft money for the lifetime of an academic grant, usually 3-5 years, so professional registration and CPD will become increasingly important to the individual technician when applying for a new position.

Technical staff, although visible locally, are invisible as a work force nationally. Professional registration will raise their status and visibility as a profession. I would encourage all technical staff working in STEM subjects to consider applying for professional registration.

Find out more about applying for professional registration.

The Royal Society of Biology is running a professional development course for technical staff in December.

Read technician’s careers profiles created for use in schools.