By Reham Badawy, PhD student at Aston University, in collaboration with Dr. Max Little, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Smartphones and healthcare

Smartphones have become a pivotal tool in all aspects of our lives, impacting the way we communicate with one another and revolutionising the way in which we shop and bank. But what could be the impact of smartphones on healthcare? Smartphones are the perfect tool for monitoring an individual’s health because we carry them around with us everywhere we go, and so we can easily measure how symptoms fluctuate throughout the day. What if smartphones could be used as health monitoring tools to detect the early symptoms of a disease?

Smartphones have become a pivotal tool in all aspects of our lives, impacting the way we communicate with one another and revolutionising the way in which we shop and bank. But what could be the impact of smartphones on healthcare? Smartphones are the perfect tool for monitoring an individual’s health because we carry them around with us everywhere we go, and so we can easily measure how symptoms fluctuate throughout the day. What if smartphones could be used as health monitoring tools to detect the early symptoms of a disease?

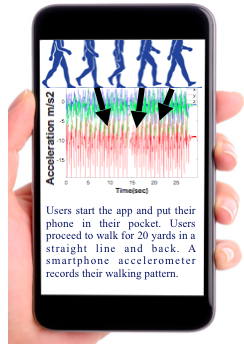

Smartphones come equipped with a large variety of sensors to enhance our user experience. A standard smartphone sensor known as an accelerometer, which measures movement, has been successful in distinguishing patients with Parkinson’s Disease from healthy individuals, solely by measuring their walking pattern.

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a brain disease which significantly restricts voluntary movement. Symptoms include slowness of movement, trembling of the hands and legs, the resistance of the muscles to movement and loss of balance. Currently, we can only detect PD when the key movement problems of the disease are apparent during the late stages of the disease. Detecting the disease early on could help us find a cure, or treatments which slow down disease progression. Interestingly, individuals who do not display any symptoms, but are at risk of developing PD (due to a genetic mutation, for example) have been found to display very subtle movement problems in their walking pattern. The ability of smartphone sensors to detect these subtle movement problems has not yet been investigated.

Using smartphones to detect PD before diagnosis

We aim to distinguish individuals at risk of developing PD from risk-free individuals by analysing their walking pattern measured using a smartphone accelerometer. Users download a smartphone app, place their smartphone in their pocket, and walk in a straight line for 30 seconds, while the smartphone accelerometer records their walking pattern.

Next, we aim to mathematically simulate the underlying neural dynamics of an area in the brain called the basal ganglia (BG), which contributes to the subtle movement problems observed in the walking pattern of patients with PD. Using this as input into a mathematical model of the mechanics of human walking, we aim to recreate the accelerometer readings from the smartphone.

Simulating the user’s walking pattern via modelling the BG, and using it as input into a biomechanical model of human walking.

Once we have recreated the user’s walking pattern, we can examine the BG model to see whether it is predictive of PD. If it is predictive of PD, and we observe subtle movement problems in the user’s walking pattern, we can classify an individual as being at risk of developing PD.

In cases in which the evidence does not match, for example, when we observe subtle movement problems in an individual’s walking pattern but the information drawn from the BG does not indicate PD, we can dismiss the results in order to prevent a misdiagnosis.

Our approach aims to provide insight into an individual’s brain deterioration through their walking pattern, so that their health status can be based on a plausible link between their physical and biological characteristics.

Follow Reham on twitter or keep an eye on her research group’s website to see how the research progresses.